Wine Business Wheel 2013

Wine Business Wheel

Introduction – Critical Supply Dynamics

Organizing around supply cycles is absolutely critical to success in the grape and wine business. No amount of marketing genius will save a brand that cannot find an adequate supply of grapes and wine of competitive quality at competitive prices. No amount of marketing and distribution muscle will save a brand that is weighted down with overpriced inventory in a flooded marketplace. Playing the cycles correctly provides a powerful competitive advantage and is often critical to long term survival in the wine business. It allows a brand not only to secure adequate supplies when prices are attractive, but also to select the best quality. Unprepared competitors then pay more, run short, and often must compromise quality when supply becomes tight. When the cycle shifts into excess, the competitive advantage becomes even greater. Brands top-heavy with over-priced supply become clumsy in the marketplace, responding not so much to consumer needs but to their own financial pressures. Brands that have planned their supply commitments correctly by understanding the long term trends, short term trends and the Global supply are able to ratchet down their cost-of-goods-sold and focus on what is working in the market rather than what is gathering dust in the warehouse.

Over the years, there has been a parade of smart marketing companies, including the likes of Coca Cola, Schlitz Brewing, and Pillsbury, who jumped into the wine business and got blind-sided by violent supply cycles. In the meantime, there was a certain family-owned winery headquartered in Modesto that has played the supply cycles well. For many years, one individual in that organization focused on marketing, which drives successful businesses. But the other individual got his boots dirty and stained his lips purple pretty much every day. He walked vine rows all over the state (a helicopter helps) and tasted wines available on the bulk wine market. He kept an eye on inventories and new plantings. During the periods when the market was awash in excess supply, he was a buyer, patiently acquiring bargains that reduced their cost-of-goods-sold. When the market became short, he would usually have an ample supply, which allowed their brands to capture market share while others were short.

Organizing around supply cycles requires three key things facilitated by this report:

• An understanding of the nature of these long-term cycles.

• The best information available about factors that can either dampen or amplify the long-term trend, including crop size and bulk wine inventories, as well as changing consumer trends.

• The confidence, supported by data, to take action while competitors are distracted by the lingering problems of the past.

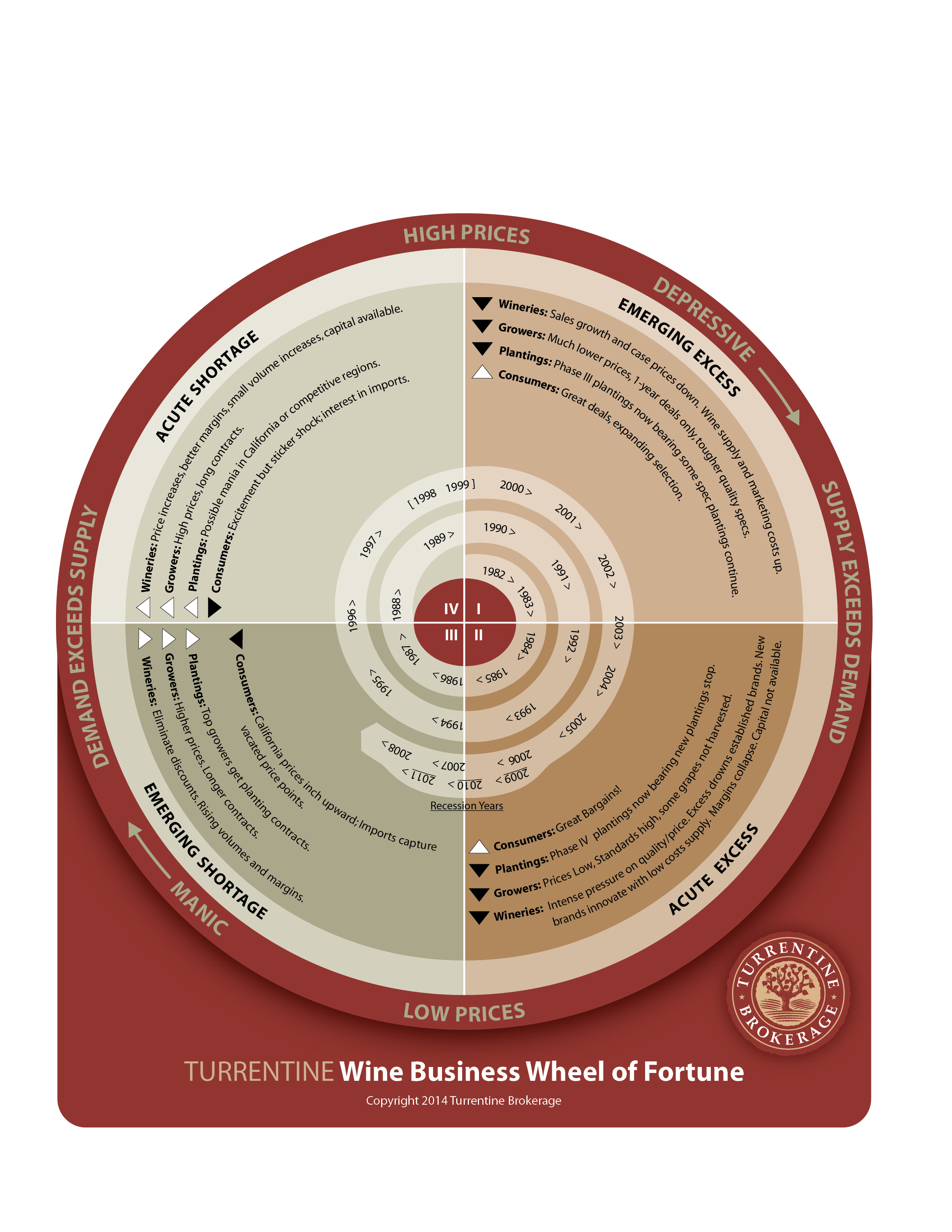

This section of The Turrentine Outlook presents the Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune®, offers some historical context, and provides some key insights into the nature of the wine business.

The Wheel Revisited

Turrentine Brokerage first published the now famous Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune in January of 1996. The Wheel is divided into four phases which characterize the 10 to 14-year supply cycles of the wine business. Phases I and II, on the right side of the Wheel, are times of excess supply, which are financially painful for growers and wineries which have not made informed supply decisions. Phases III and IV, on the left side, cover the period of supply shortage, which tends to be the best time for growers and wineries, but which is much better still for those who have positioned themselves to take advantage of the cyclical opportunity. Many wine business veterans have acknowledged that the Wheel provides a good explanation of the wild rides they have experienced over the years. The Wheel also has proven to have good predictive value. The Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune has been referenced by Wine Business Monthly, the U.C. Davis School of Business, California State University, San Luis Obispo, Sonoma State University and many other leading wine business institutions around the world.

The Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune® is subject to modification from outside influences. An incredibly powerful force, in fact, is currently at work, flattening the Wheel, making it into more of an oval than a circle. This is the force of intensifying global competition. Economic reforms around the world have unleashed the power of free enterprise. Technological improvements, especially in communications, and free trade agreements that reduced the barriers to cross-border commerce have created a new playing field for wine and just about everything else.

In the meantime, American wine consumers, especially younger consumers, have become much more adventuresome. They are willing to try wine from anywhere and there are many places in the world that can grow grapes and make wine for a much lower cost than California. California growers and vintners must respond with research to improve yields and quality of both grapes and also continue to lead the world with great marketing.

Imported wines captured their largest share ever of the U.S. wine market the last few years. As the economy continues to slowly improve, sales are likely to outpace supply and stimulate new planting domestically and globally and the re-working of older plantings to become more quality-competitive. It could take many years for supply to catch up with growing global demand.

This global supply is working to flatten the wine business cycle and to make each of the various phases last longer. As Phase III shortages developed recently, for example, the ability to substitute imported wines flattened the cycle by preventing retail prices for California wines from escalating as high and as fast as they have done in the past. Smaller increases for California wine prices translate into smaller increases for grape prices. Coupled with the increased cost of vineyard development, the smaller increase in grape prices may result in more modest planting than in past cycles. As long as consumer sales continue to grow, slower and more modest planting will probably contribute to a longer cycle. Depending on what happens with sales growth, it may take six or more years for new plantings to catch up with, and finally get ahead of, growing sales. This means that the total cycle is now more like 12 or 14 years rather than the old eight to ten years.

Key Factors that Shape Wine & Grape Supply Cycles

There are two forces that drive the wine business cycle, one of which is based on the nature of grapevines and the other is based on the behavior of wine consumers.

Cycle Factor I: Expensive, Slow-growing Vineyards

The first factor is the slow response of the wine business to changes in supply and demand. This response is painfully slow in reaction to both excess and shortage. Over-production plagues most business occasionally and most non-wine businesses cut production quickly in order to reduce the expensive problems of excess inventory. But when a grower or a winery has invested $15,000 to $35,000 per acre in development costs for a new vineyard, they are very slow to call in the bulldozers. Some acreage, particularly low-yielding acreage, does come out but, for the most part, growers keep on farming, trying frantically to sell their grapes and hoping that prices will stabilize. In the meantime, newly planted vineyards start maturing and mature vineyards keep on producing more grapes than needed, which results in excess supplies of bulk wine (Phase I). Prices drop for grapes and wines in bulk, resulting in big losses. New plantings finally grind to a halt. Discounting becomes rampant in the retail market (Phase II).

The excess supply, on the other hand, sparks creativity among marketers, who figure out how to attract consumers. It also allows winemakers to improve quality by enforcing exacting standards on grape sellers and selecting carefully among vineyards and bulk wine lots. In addition, sales people are able to open new markets with bargain wines. Sooner or later, increases in vineyard production level out and the new marketing spurs sales growth. At some point, this growing demand drinks up the excess supply and the wine business lurches into shortage (Phase III). In most businesses, when demand grows faster than supply and the market signals that more product is needed, companies quickly gear up production to meet demand. But not in the wine business, where wineries in the short term may import bulk wine and in the long term wineries and growers have to put grapevine cuttings in the ground no matter where in the world and wait. And wait. It takes about three years from planting until the vines start producing a commercial crop. Adding in a year to get permits and financing, and it can easily take four years from the market signal to the first significant increase in production.

If demand continues to increase during this time, limited supply will be allocated by increasing prices. Increasing prices, in turn, encourage additional plantings. These additional plantings, which can go into any patch of earth around the globe that can produce competitive quality at a competitive price, also take three or four years to begin producing, so there is plenty of time for prices to continue to escalate before the new production starts to catch up with demand. The more that demand outstrips current production, the higher grape prices go. The higher grape prices go, the more acres of new vineyards get planted (Phase IV). Sooner or later, those new plantings will catch up to and surpass demand and the cycle will make the transition – painful for those who do not know it is coming – to Phase I excess.

Cycle Factor II: Consumer Behavior & Price Inelasticity

This whole cycle is made more violent by a second factor. In the United States, at least, demand for varietal wines appears to be fairly price inelastic. That economic term means that variations in price do not influence demand as much as one might expect. When grape supply becomes short and prices for grapes and wines increase (Phase III and IV), most wineries allocate limited supply by raising prices, or they simply shift inventory to higher-priced brands. But what many brand owners find – to their delight – is that most of their competitors are doing the same thing and demand does not fall off very much. So they raise prices again and often find that their wines remain on allocation. These price increases typically produce substantial increases in margins as casegood prices go up more than grape prices. Margins often expand to the point that the whole risky, capital-intensive business of making and marketing wine starts to make excellent financial sense. Suddenly, banks and investors are ready to fuel an exuberant expansion of vineyard and winery capacity in California or in competitive regions worldwide.

But, alas, price inelasticity is not so much fun on the downside. As all of the new plantings come into production, sooner or later supply exceeds demand and winery inventories begin to back up (Phases I and II). When one brand seeks to move excess casegoods by dropping price, they are usually able to steal market share from other brands. But these lower prices do little to increase total consumption. In fact, studies seem to show that, even when prices have fallen to $1.99 per bottle for premium varietal wines, as they did with the extreme value brands, there is only a limited amount of new consumption. While there is some expansion of use occasions and some incremental gain in consumption, most of the consumption of extreme value wines seems to be as a replacement for higher priced wines. This price inelasticity on the downside is devastating to the whole margin structure of the business.

When extensive new plantings come into production, they push the wine business into excess and many brands are forced to discount prices in order to deplete swollen inventories. Retailers play one producer against another and the margin structure of the business contracts. Banks become conservative and investors keep their wallets closed. The planting of new vineyards pretty much stops and some existing vineyards, particularly those with marginal yields or out-of-favor varieties, may be removed. Large quantities of wines in bulk get blended into super bargain wines, sold into low-cost export markets and are distilled for brandy. Necessity and opportunity, however, get creative juices flowing and marketers start to conjure up new brands that will tickle the consumer’s fancy. This creative effort usually succeeds in stimulating demand just as production levels out because of a lack of new planting. Before long, sales consume the excesses and the wine business again enters Phase III, the beginning of shortage.

History of the Past Two Complete Cycles

Major wine brands have often been born during periods of excess supply (Phase I and II), a time when new brands have an advantage over many established brands because established brands are stuck with excess inventories and high costs. The new brands can usually purchase grapes and bulk wine for bargain prices, sometimes at prices less than the cost of production. This allows new brands to invest in creative marketing and/or offer exceptional quality for the price. They can also target what the market wants now while many established brands are focused not on the consumer but on what needs to be sold in order to get bankers and investors off their back. The critical importance of correctly playing the wine business cycle can be illustrated by following some key brands from their inception through the ups and downs of the last two cycles, focusing on Glen Ellen for the first of these cycles and Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone for the second cycle.

The Glen Ellen Cycle: 1982 through 1989 (Phases I-IV)

A wave of new production flooded the California wine business starting with the large harvest of 1982, pushing the wine business into Phase I oversupply. Among those brands invented to take advantage of this excess, perhaps the most famous is Glen Ellen. Conceived by Bruno Benziger and his son Mike, and supported by the extensive Benziger clan, Glen Ellen was created as a label intended to keep the family busy and to strengthen distributor and retailer relationships while the high-end Benziger brand was being developed. Fueled by abundant supplies of wine available at bargain prices on the bulk wine market, Glen Ellen took off like a rocket and created the category that became known as fighting varietals. Extensive new plantings, especially of Chardonnay, were coming into production and Glen Ellen was there to provide a new route to market, although not at the prices which many vineyard investors and bulk wine sellers had hoped. But Glen Ellen and similar brands encouraged Connie and Conrad Consumer to trade up from red, white and rosé jug wines to Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and White Zinfandel in cork-finished 750 ml bottles. The wines were “Private Reserve” no less.

By 1986, increasing consumer demand for fighting varietals was beginning to catch up with supply and grapes and bulk wine prices began to escalate. This, in turn, stimulated new plantings, but it would take three or four years for those new plantings to start to bear grapes. In the meantime, wineries found it easier to sell their casegoods. Many began to eliminate discounts and to take some price increases. As sales growth continued and competition for grapes and wine intensified (Phase IV), Glen Ellen and others began to sign high-priced, long-term grape contracts, confident that they could pass increased costs on to the consumer. Then came the crush of 1989, where the cycle turned with a vengeance into Phase I oversupply. In fact, just about everything went wrong that could go wrong. Grape prices were at record highs, the crop was huge, and it rained repeatedly just before harvest, creating major quality problems. In the same general time period, several other things went wrong as well: a substantial excise tax increase was passed, DUI laws were tightened in California and other states, sulfite warning labels were required, tin-lead capsules were banned, and there was bad news published about alcohol consumption and health. The rate of retail sales growth slowed dramatically just as a big crop and new acres overwhelmed the market. Excess supplies and declining retail prices prevented brands from raising prices even enough to cover the increased excise taxes, much less to cover the high-priced grapes purchased under long-term contracts. The Glen Ellen brand was sold to Heublein / Grand Metropolitan in 1993 for an amount reported to be between $60 and $80 million.

The Kendall-Jackson & Blackstone Cycle: 1990 through 2000

Phases I-II

Many brands were launched on the high tide of Phase I and II excesses in early 1990. Perhaps the two iconic brands of the time would be Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone. As the Glen Ellen brand helped move consumers from Red, White and Rosé to Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and White Zinfandel, Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone helped move consumers to a higher level of premium varietal wine. Like Glen Ellen, Kendall-Jackson built its reputation on Chardonnay but also branched out to other varietals as well. Blackstone, of course, rode the Merlot wave to fame and fortune. Both Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone survived the inevitable cyclical crash in good shape because they both heeded the lessons of the Wine Business Wheel of Fortune and prepared for the striking changes of Phases I and II.

Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone both took advantage of the huge excess of grapes and bulk wines that flooded the wine business in 1990, 1991, 1992, and 1993 (Phases I and II). They were able to purchase grapes and wines on the spot market at prices significantly below the prices most brands were paying because most brands had made long term contracts in 1988 and 1989, at the very height of the market. While most brands were hamstrung by a high cost-of-goods-sold, Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone and other new brands were offering innovative, high quality wines at attractive prices and focusing on the varieties that were hot in the market. Consumers responded enthusiastically and sales growth began to accelerate.

Phases III-IV

As the market began to tighten up in 1994 (Phase III), most established brands were still obsessed with the problems of excess and were skeptical about the prospects of a shortage. They avoided long-term commitments even as the grape and bulk wine markets began to firm up. Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone, on the other hand, looked ahead (according to predictions of the Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune) and changed their strategies as the supply situation changed. They began to make long-term contracts to tie up supply while prices were low. Kendall-Jackson also began to purchase and replant vineyards at attractive prices. These strategic moves provided the brands with ample, attractively-priced supplies when the grape and bulk wine markets tightened up. They were therefore able to make distributors and retailers happy while many competing brands were forced to decrease quality, increase price, and allocate insufficient supply.

This period of shortage of supply in the wine business (Phase III and IV), 1994 through 1999), happened to coincide with what Dr. Robert Smiley of the U. C. Davis School of Business has described as the greatest wealth creation event in the history of the world, the Silicon Valley High-Tech Boom. The employees and investors who most profited from the High-Tech Boom happened to be a perfect demographic for high-end wine and the premium wine market began to grow at remarkable rates, restrained only by insufficient supply. Many brands took multiple price increases and still remained on allocation. Many folks got caught up in the euphoria and were convinced that prices would continue to increase for the foreseeable future. With profits strong and marketers crying for more product, most wineries committed to long term grape and bulk wine contracts at record high prices. Vast amounts of capital poured into the wine business and new vineyards and winery expansions sprouted everywhere. A few brands, however, took note of the extensive new acres, remembered the cyclical nature of the wine business and avoided long-term commitments in Phase IV, at the top of the Wheel.

Bonus Years

In 1997 some of those new acres were beginning to bear fruit and Mother Nature served up a huge yield per acre. The result was a tsunami of grapes. Bulk wine prices fell about 50%, from astronomical levels to levels that were still high by historic standards. The over-heated grape market slowed down, although most grapes were already contracted for multiple years. It appeared that the Phase IV boom had ended and the Phase I oversupply was starting. But extraordinary circumstances halted the transition at a point that was well below the peak of the market but which proved to be a very strong market nevertheless, resembling a Phase IV shortage more than a Phase I excess. This good fortune resulted in two bonus years, 1998 and 1999, near the top of the cycle. This was caused by continued strong growth in premium wine consumption and by light crops in both 1998 and 1999. This extra time at the top was great for the wine business at the time, but it pretty much guaranteed a slower turnaround at the subsequent bottom.

The problem resulting from two extra years of relatively short supply and strong demand was that the planting boom continued longer than it otherwise would have. Caught up in the continuing euphoria of the times, people kept planting new acres during these bonus years. In fact, carried along by the momentum of long-term decisions, some folks continued planting even after the high-tech boom blew up in March of 2000 and a large 2000 harvest, with many new bearing acres, pushed the industry into Phase I excess. According to the Acreage Report of the California Department of Agriculture, for example, optimistic (or uninformed) investors planted 4,487 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon in 2001. Even after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 impacted the economy, investors reached into their wallets to plant 2,814 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon in 2002, apparently oblivious to the fact that the quantity of Cabernet Sauvignon offered for sale on the bulk wine market had swelled to almost six million gallons, with few buyers and plunging prices.

Back to Excess, Phases I & II

With the harvest of 2000, the delayed crash finally arrived. An above average yield per acre, multiplied by significant increases in bearing acres, produced a record crop. In the meantime, the high-tech boom had gone bust and the rate of casegood sales growth slowed. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and the Enron, WorldCom, and Global Crossing accounting scandals further impacted the market. The California wine business sank into a huge and extended excess supply in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 (Phase I and II). Most brands were saddled with contracts for far more supply than they needed, and at far higher prices than made economic sense, in the new, viciously competitive case good market. Grapes without contracts became very hard to sell, even from well-regarded vineyards. The bulk market was flooded with supply. Large quantities of bulk wine were sold for export at very low prices. Bronco Wine Company launched its Charles Shaw brand and became one of the few domestic buyers on the bulk wine market. It is safe to say that no one got rich selling wines on the bulk market during this period.

Both Kendall-Jackson and Blackstone actually weathered the market crash in good shape. Blackstone, in fact, makes a great case study of the value of playing the market cycles. Blackstone had timed its grape and bulk wine contracts so that they began expiring during the same period that the market began to soften (1997 through 2000). This allowed them to take advantage of lower grape and bulk wine prices and improved selection. This created an important competitive advantage when most of its competitors were struggling under the weight of excess supply locked in at high prices for many years. Blackstone’s ability to preserve margins by lowering raw material costs was no doubt a significant factor in achieving the $140 million price that the brand commanded in its 2001 sale to Pacific Wine Partners (a partnership later absorbed by Constellation Wines).

The Extended Excess, 2005 & 2006

The major brands managed to whittle down their excess supply, taking huge losses in the process. Growers also took big losses, with many tons sold way below cost and significant tonnage left on the vine. Substantial acreage was removed in the Southern San Joaquin Valley. But this bitter medicine appeared effective and it looked like the market might recover faster than we had originally anticipated. Heading into the 2005 harvest, bulk wine inventories were lower than they had been in many years and the rate of casegood sales growth was picking up. The beginning of a recovery seemed near at hand. But the huge yield per acre of the 2005 harvest, augmented by new acres planted late in the cycle, completely overwhelmed growing sales. In fact, you could say that the huge harvest of 2005 actually made the Wine Business Wheel of Fortune turn backwards, plunging the California wine business back into serious excess supply. Hopeful expectations that the 2006 harvest would be light after such a big harvest in 2005 did not materialize.

Transition… and Recession, 2007 through 2011

Despite continued growth in sales, the wine business continued to suffer from some excess inventories in most varieties through the harvest of 2007. The light harvest of 2008, however, was a huge help, allowing many wineries to balance inventory even though the recession was already hurting sales growth above $10 per bottle. As the recession persisted into 2009, however, retailers and wholesalers cut inventories as much as possible and consumers throttled back on restaurant purchases and traded down in price-point. These effects of the continuing recession, plus a relatively large crop in 2009, put tremendous pressure on premium wineries and created a discount-dependent retail market. These tough realities were reflected in a difficult grape market for the 2010 harvest, particularly at higher price points.

The recession generally helped wines selling for less than $10 per bottle and hurt sales above $10 per bottle. The biggest producers were able to take advantage of creative marketing departments, economies of scale, distributor consolidation, and their financial wherewithal to seize additional market share. As supplies in California tightened, many of these brands were able to access global supplies at competitive prices. Large quantities of imported bulk wines, including red blenders, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Grigio and Moscato, kept many formerly California brands growing. This is not all bad news for California growers, however. As the California supply of some of these varietals has begun to increase, many of these brands have already switched back to California wine and more will do so in the near future.

As the economy gradually improved in 2011, 2012 and early 2013, consumers slowly began trading up once again. The fastest sale growth in the U.S. market has now shifted to brands retailing at $10 per bottle or more. There has already been significant planting in the interior regions of California, mostly under contract to large producers. Planting in coastal areas has been much more restrained. Growing sales and a light harvest in 2011 created a shortage of supply and convinced many brands to raise price or to reallocate supply to higher priced brands. A large crop in 2012, however, eased supply constraints. The race is now on between a recent increase in planting, which will gradually increase average crop size, and a slow but steady increase in consumer sales. Overall, we expect consumer sales to increase faster than average production for a few years and growers and wineries will need to be mindful of Global competition to make sure that sales of California wine continue to grow to keep up.

Post-Recession, 2012 through Present

Based on the nature of grape vines (capital intensive and slow to bear) and the nature of humans (alternating between greed and panic), The Turrentine Wheel has been an effective predictor of wine business supply and demand trends for many years and through several supply cycles.

The cycle The Wheel describes, however, requires growth in consumer demand in order to progress through its phases, eventually draining swollen inventories during periods of excess and stimulating planting during periods of shortage. The past cycles described above enjoyed casegood sales growth for premium varietal wines at fast enough rates to carry along almost all premium varieties grown in all regions of California. Some varietals and areas have obviously done better than others, but the situation among varietals has usually resembled a horse race: some ahead and some behind, but almost all varieties in the same quarter of the track. Currently, however, the overall growth rate – perhaps due to the anemic economic recovery – is not strong enough to carry all varieties.

There is a major disconnect, intensified by two large crops in a row, between the interior regions and the coastal areas, which are now experiencing different phases of the cycle. The interior regions enjoyed strong sales growth as consumers traded down during the recession. This promoted both planting and a turn to global sourcing. As the planting began to come into production, consumers started to trade upscale and supply outpaced demand for interior grapes and wines. This has been partially offset, however, by the effects of brands that have switched back from imported bulk wine to California grapes and wine.

What happened in the interior is very different from what has happened in the coastal areas, which suffered declining sales as consumers traded down during the recession. While there has been significant planting in the Central Coast (mostly Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir along with some Chardonnay), the North Coast has had little planting in excess of replacement. Growth in the $10.00 to $20.00 per bottle range has resumed. After two large harvests in a row, there is currently plenty supply for most varieties. Sustained growth in the $10.00 to $20.00 per bottle range will eventually drain current supply and require more vines to be planted.

The upshot of all of this for the Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune is that the state of the entire premium varietal wine business can no longer be described, with slight variations, in terms of one inclusive cycle. Different varieties and, to some extent, different regions, are experiencing a wide variety of growth rates and supply challenges and need their own Wheel. Merlot, for example, is actually declining in retail sales while Pinot Noir continues with strong growth. It is possible that retail sales growth for premium varietal wines could accelerate to such a level that demand for just about all varieties could get ahead of supply, allowing all wine to fit in close proximity on one Wheel. Unless and until that happens, however, the well-known an all-inclusive Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune is not going to specify a general position in the cycle for the premium varietal wine business as a whole beyond 2008. For subsequent years, The Turrentine Outlook© will continue to analyze the supply demand cycle for each varietal in the Where on the Wheel section and throughout the varietal commentary. With this current market dynamic, it is more important than ever to have a full understanding of supply and demand in your area, in competitive areas, and for substitute varieties.